- Evolution

of classical music since the early 20th century, changes the good

and not so good.

Art

is an embodiment of the creative energy of people and a reflection of their

social environments. Reflecting the devotional life of the people in the Vedic

period, the Sama Veda hymns, employing no more than three swaras, never failed to create an august atmosphere.

Later,

the patronage of kings and feudal lords nurtured the tradition of classical

music. Learning at the feet of the preceptor went on till the beginning of the

Second World War.

The

growth of natural sciences in the Western world and the industrial revolution

in India after World War I fostered a mechanistic way of life and a

materialistic sense of values. The age of commercial art dawned. India leaned

more and more towards urbanisation and an indiscriminate acceptance of the

social and moral values of the West. This did not fail to cast its shadow on

Indian classical music.

In

the whirl of democracy and the zeal for the formation of a classless society,

feudal lords and princes who were the main bulwarks of classical music, melted

away and music was left at the mercy of the masses for patronage and survival.

The rare charms and aesthetic delights of music that flourished in the select

assemblies of appreciative critics and connoisseurs, could no longer be

enjoyed.

Then,

the idea that the aristocratic organisation of society was a prerequisite of

high culture, came under severe criticism.

First published in

Journal of Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

“The fact that culture requires leisure is, however, hardly a sufficient justification for the maintenance of a leisure class. For every artist which the aristocracy has produced and for every true patron of art, it has supported a thousand wastrels.

An intelligent society will know how to subsidise those who possess peculiar gifts in the arts and the sciences and free them from the necessity of engaging in immediately useful toil.” (Reinhold Niebuhr: Moral Man & Immoral Society).

This

logic appears to be plausible provided a society can discriminate between real

and pseudo art. Artistic excellence is incompatible with an artiste struggling

for his bread. It was a stupendous achievement of Pandit Vishnu Digambar

Paluskar that he made classical music more broad-based and democratic. But he

meant that it should not pursue cheap popularity.

In our zeal for making everything secular, we are making

classical music profane and vulgar.

In the words of Will Durant, “The spread of industry and the decay of aristocracy cooperated in the deterioration of the artistic form. When the artiste was superseded by machine, he took his skill with him and when the machine was compelled to seek vast markets for its goods, adjusted its products to needs and tastes of vast majorities, design and beauty gave place to standardisation, quantity and vulgarity. Had an aristocracy survived, it is conceivable that industry and art might have found some way of living in peace.

The taste of innumerable average men became the guide of the manufacturer, the dramatist, the scenario writer; the novelist and at last of the painter, the sculptor and the architect; cost and size became the norm of value and bizarre novelty replaced beauty and workmanship as the goal of art. Artistes, lacking the stimulation of an artistic taste, sought no perfection of conception and execution, but aimed at astonishing effects. Music went down into the slums and factories to find harmonies adapted to the nervous organisation of elevated butchers and emancipated chambermaids. But for automobiles and cosmetics, the 20th century seemed to promise total extinction of art”. (Mansions of Philosophy).

The

melodic character of Indian music cannot stand harmony which implies a

combination of discordant notes simultaneously played. The raga has a melodic

structure. Swami Haridas and the famous composer Thyagaraja, we are told,

attained a state of eternal bliss (Savikalpa

Samadhi) through the medium of swaras. This was the outcome of their

individual excellence. Democratisation of music has, on the other hand, led to

a lowering of standards.

The

attainment of aesthetic delight, i.e. sundara,

must always be accompanied by an emotional purification or liberation, i.e. shiva, and both these elements lead to

final beatitude or the elevation of the human spirit, i.e. satya. One can imagine that these ideals in classical music cannot

be attained by the production of music for commercial purposes or catering to

the mob.

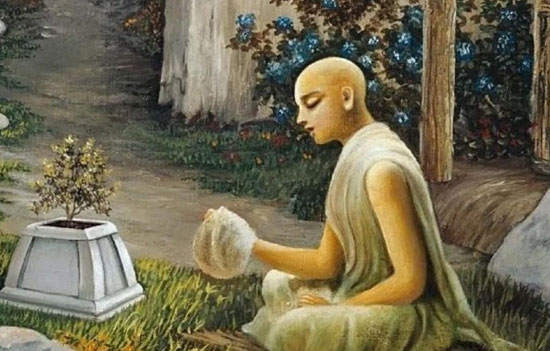

Swami Haridas

Swami Haridas

Creation

of rasa is the goal of raga and this calls for a refined and

correct tune or shruti. The artiste must get the shruti correctly and understand the full impact of the text of the

song he performs. But a modern artiste seldom pays heed to them. He hankers

after spectacular effects by crude methods. He never worries to see if a note

is correctly and effectively used. Even the major notes are uttered in a crude

fashion, not to speak of the subtle micro-tones. The modern listeners in the

big industrial cities go to a concert more out of fashion than out of any love

or understanding of music. It is important for the growth of classical music

and its true appreciation that the artistes do not stoop to find favour with

these pseudo-lovers of music.

The

use of machines in the sphere of classical music has its own limited

importance. The invention of gramophone and sound-recording no doubt conferred

a unique advantage on mankind. It made possible the preservation of the

creations of the old masters. Who would have benefited from the divine music of

Swami Haridas, Tansen or of Rehmat Khan, Bhaskar Bua and Vishnu Digambar, had

it not been preserved with the aid of the machine? But the replacement of the

human voice by the metallic ring of the machine has had a nefarious effect on

the human ear and soul.

Lewis

Munford corroborates the same view in his book, The Arts. “The perfection of mechanical transmission and the spread of music through radio and phonograph may presage extinction of music as a direct spiritual experience...if the process of mechanisation is unfriendly to the human spirit, it will be inimical to music; in the long run, the spirit must either assert itself or commit suicide.”

The

Sugam Sangeet or light music, which

harnesses musical material to lyrics for utilitarian ends, is also an outcome

of the mechanistic values that have corroded the mystic world of melody.

Popular music is being pushed into the market as a source of profit and as a

momentary escape from the miseries of a mechanical civilisation.

Films have played a potent role in the debasement of classical

music.

Film

music is a hybrid, which partakes of the characteristics neither of Indian

classical music nor of Western popular or classical music. Giving no more than

a casual, fitful sensation, the flippant and frivolous film songs have led to a

fall in the standards of artistic quality.

Artistic values will not improve automatically. The time has come for all lovers of classical music to rally together to fight these evils. It is necessary to make every effort to resuscitate classical music—one of the finest achievements of mankind.

This article was first published in the Bhavan’s Journal, May 31, 2022 issue. This article is courtesy and copyright Bhavan’s Journal, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Mumbai-400007. eSamskriti has obtained permission from Bhavan’s Journal to share. Do subscribe to the Bhavan’s Journal – it is very good.

Also read

1.

Thayagaraja,

musician par excellence

2.

What

is a RAGA