To read PART 1

KOREGAON

: 1 JANUARY 1818

The Maratha forces led by Peshwa Baji rao II and two battalions of the English came face to face on New Years’ Day in the year 1818. The Peshwa was fleeing from his pursuers while asking other chiefs to raise their armies and take a stand against the English. A victory against any English force at this critical juncture could change the morale of the general populace, the course of the war and the fate of the beleaguered Peshwa and his army…

The Peshwa’s army reached Koregaon around 31 December from Phulshahar about four kilometres away. The army was refreshed from its rest at Phulshahar and the later assertion in an English letter that the plain was ‘white’ with the Maratha horse was merely a way of saying they had changed and worn freshly washed clothes. They camped across the high road towards Pune blocking the path of the English force that was to arrive from Shirur. They knew that General Smith was still in pursuit somewhere between Sangamner and Chakan.

In response to Colonel Burr’s demand for troops to protect Pune, Captain FF Staunton was dispatched from Shirur, then commanded by Colonel Fitzsimon. They left Shirur at about 8 pm on 31 December and marched overnight a distance of twenty-eight miles till they reached Koregaon on the river Bhima. The troops were drawn from three different units as under;

-

600 men of the 2nd Battalion

of 1st regiment of the Bombay Native Infantry.

-

A detail of the Madras Artillery with

two six pounders and twenty two European gunners, and

-

About 300 of the Poona Auxiliary Horse

led by Lieutenant Swanston

Accompanying

Staunton and Swanston were Lieutenant Chisholm, the Adjutant Lieutenant

Pattinson, Lieutenant Connellan, Lieutenant Jones of the 10th

Regiment but doing duty with 2nd/1st, and two surgeons

Wingate and Wylie.

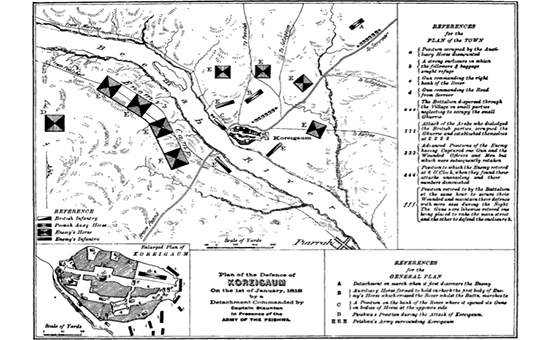

Map of Battle of Koregaon

Map of Battle of Koregaon

The

narratives of the battle fought between the Marathas and the English force

under Staunton on 1st January 1818 are in original letters of the

times, written soon after the battle.

In Staunton’s own letter written on 3rd

January 1818 from Shirur, he reports,

‘Having proceeded on my way towards Poonah, as far as Corygaum by 10 A.M. on the 1st January my further progress was arrested by the appearance (according to information then obtained) of the Peishwah, with a very large Army, supposed to be about 20,000 Horse and 8,000 Infantry, with two heavy Guns; the whole formed on the opposite side of the River Beemah

ready to attack us. I continued my march

till I reached the Village of Corygaum, in which I determined to make a stand,

and according took post, selecting commanding situations for our two Guns. The

enemy perceiving my intention sent 3 different bodies of Arabs, consisting of

about 1,000 each, under cover of their Guns, and supported by large bodies of

Horse for the same purpose; and I am

sorry to say from their superior information of the nature of the Village succeeded in getting hold of its

strongest post, and from which I was unable to dislodge them during the day; we

continued incessantly engaged till 9

P.M. when we finally repulsed them.

At day

break on the morning of the 2d we took possession of the post the enemy had occupied

the day before, but they did not attempt to molest us. On the evening of the 2d

despairing of being able to make my way good to Poonah, and my men having been

48 hours without food, and no prospect of procuring any in the deserted Village

we had taken post in, I determined upon the attempt to retreat ; and having collected the whole of the wounded,

secured the two Guns and one Tumbril for

moving, I commenced my retreat at 7 p.m. being under the necessity of destroying one empty Tumbril, and leaving the

Camp Equipage; under this explanation I trust I shall be deemed justified in

the steps, I have taken; Our loss has

been heavy indeed, but not more so than might naturally be Expected in a struggle like this, and is as follows,—

1. Killed Lieutenant Chisholm Artillery, and Assistant Surgeon Wingate of 2d / 1st Regiment N.I.

2. Wounded - Lieut. Pattinson - dangerously. (Note –he died of his wounds later) and Lieut.

Swanston - but not dangerously.

3.

50 Men Killed 2d Battalion 1st Regiment N.I.

4.

12 Men Killed Artillery.

5.

Total Killed - 62 Men (Auxiliary Horse, not included.)

6.

105 Men Wounded 2d Battalion 1st Regiment N. I.

7.

8 Men - Artillery.

8.

Total Wounded 113

9.

Total Killed and Wounded 175 Men (Auxiliary Horse not included.)

(However, Surgeon Wylie gives figures of

111 killed and 149 wounded for a total of 260 killed and wounded. This is in

contrast to just 31 killed from the English armies in Khadki and Yerawada

combined.)

In concluding this report, I beg to assure you, that it is utterly impossible for me to do justice to the merits and exertions of the European Officers, Native Commissioned, Non-Commissioned Officers and Privates, that I had the honour and good fortune to command on this trying occasion’.

The Peshwa’s Arab infantry attacked the village and forced the English force into one corner of the village. They captured one of the two guns for a while but did not hold it for long. Desperate bayonet charges to protect their position and the wounded in their ranks even by the surgeons in the army during this fierce fight in the narrow lanes of the village continued all day. In the first hour a musket shot to Lt. Chisholm’s head killed him. The Arabs came up and cut off his head meaning to present it to the Peshwa across the river as a trophy.

Trimbakji Dengle and Gokhale directed

the battle and for a short time Trimbakji may have crossed the river. Bapu Gokhale,

who had just lost his son due to an illness four days back put his personal

tragedy behind and geared up for fight. Numerous horse of the Peshwa cordoned

off the village cutting off all avenues of escape for the English. The

remaining cavalry stood on the plain opposite. As assistant Surgeon Wylie

writes,

‘The army of the enemy was the grandest sight I ever witnessed, and consisted of 20,000 Horse and between 2 and 3000 Infantry, supported by two guns..’.

When Asst. Surgeon Wylie wrote of the

battle later, he gave a narrative that gives us a few more details,

‘…(We) were ordered to march at 8 p.m.; we accordingly moved with the intention of proceeding to Poonah to reinforce the troops

there; we marched all night and were getting quietly on till within two miles

of the Village of Corygaum, when we observed the enemy in great numbers on the south bank of the

Beemah; the immense army did not prevent our reaching the Village about 11 am.,

but we had scarcely done so, when we

found ourselves surrounded completely by Horse, and at the same time

attacked by upwards of 2000 Infantry, chiefly Arabs, who gained possession of the best part of

the Village, for their mode of

warfare; we had an elegant post for one gun; the other gun was much exposed to the fire of the Arabs, and it was

at it, where the majority of the Artillerymen killed, met their fate, as also

my much lamented friend and chum, poor Chisholm, who fell I think during the

first hour. The first mentioned gun was kept in play from 11 a.m. until dark,

and did a great deal of execution, not only among the Arabs, but among the

large bodies of troops in the plain;

from the nature of the situation in

which the other gun was placed, it became at one time in the power of the enemy, who did not

attempt to secure it; the truth is, they were driven back before they had time to think of it; in this way we

continued the whole time, sometimes losing, and sometimes gaining ground, or

rather the possession of Pagodas and houses. Swanston who was wounded twice very early in the day, I took to a Pagoda, dressed him, as also Lieut. Connellan and some others, but I did not remain long, finding it absolutely necessary to render the two remaining Officers all the assistance in my power in another way. Assistant Surgeon Wingate was wounded after, in attempting to leave the Pagoda; he returned to it, and shortly after the Arabs surrounded it and entered. Wingate met no quarter; Swanston and Connellan with the Serjeant Major of the 2d Battalion 1st Regiment were stripped of their all, excepting shirt and trousers — fortunately for them a charge was made, which drove the Arabs back and the place was recovered. At 5 p. m. only six Artillerymen remained for duty, out of 27— 12 killed, 8 wounded, and one unfit from sickness. The 2d Battalion 1st Regiment had lost upwards of 50 in killed and 100 wounded. The Auxiliary Horse suffered severely. In the afternoon we were in a dreadful state for want of water, and continued so until dark’.

Wylie continues his narrative about the Peshwa’s army and comments on Brigadier General Smith’s orders that appear to be overstating the case for the English;

‘The Peishwah, Gockla and Trimbuckjee, were present.

A

very flattering order has been issued by General Smith, on the conduct

of the Detachment

— in detailing the business, it is mentioned,

that the Village was abandoned

by the enemy during the night, but I assure you, that many of the Infantry were

still in, between day-break and sunrise;

before the latter, they were entirely driven out, and during the course of the

second day disappeared, Horsemen and all; that day I went to work with the wounded, and you may easily imagine my situation commencing on such an important duty, almost worn out from the fatigues of the preceding day. Captain Staunton deemed it advisable to return to Seroor, which was accompalished by 9 a.m. of the 3d, - having started at 7 pm of the 2d.

I might

write from morn till night on this business without adding anything new - the

characteristic of the conflict was an incessant firing from 11 a.m. until 9

p.m., between the Arabs and the Detachment— frequent charges by the latter— and ground lost and won often during the day—while the plain around was white* with Horsemen’. (*by this he clarifies that the Peshwa’s army was in their newly washed clothes as if they were celebrating a festival.)

The Peshwa along with the Maratha king

were watching the battle from the other side of the Bhima. Here, the Peshwa saw

the Chhatrapati had opened his ‘abdagiri’ (a kind of screen from the sun) and warned him that it would prove to be a target for the English.

A few matter of fact Marathi letters describes the battle at Koregaon,

‘Passing the fort of Chakan; there were two English there, we arrested them and brought them to Phulgaon. Here we heard the English were sending two ‘paltans’ and were coming to Koregaon. We attacked them, the English too responded, there was a battle, we cut up two of their ‘paltans’ took cannons and marched towards Jejuri..’.

Another letter mentions the battle in

these words,

‘The Shrimant is at Rajewadi near Jejuri. Trimbakji Dengle took the fort of Chakan. The men from the ‘Redfaced’ (English) within were cut down. They were then at Phulgaon. On Thursday they marched to Koregaon. One and a half paltan of the

English came there with cannons. When they fired, our forces attacked them and entered the village. Our army entered the village and cut down the one and a half paltans and about three hundred men. One of their chiefs’ head was cut off’.

A similar report is seen in another

Marathi letter,

‘..the English took refuge in Koregaon. They fired a cannon. Then Gokhale, Raste and others went on foot and defeated them. One of their platoons and one cannon found shelter in a strong building in Koregaon and they escaped. We captured one cannon and one platoon was cut down’.

During the entire day, the injured and trapped English battalion was offered no quarter. A section of the force wished to surrender, to which Staunton “represented the forlorn prospect of a surrender to a cruel and barbarous enemies (sic), pointing out how Lieut. Chisholm had been treated and telling them ‘such was the way all would be served, who fell dead or alive in the hands of the Mahrattas’, on which they declared ‘they would die to a man’. The fortitude and staunch defence of

the English force was thus reinforced with the realisation that surrender

meant certain death.

On the night of the 1st January 1818, Staunton felt his situation was desperate. He sought help and decided to send a letter to Col. Burr at Pune. The messenger belonged to the Poona Auxiliary Horse and had to pass through the Maratha cordon. ‘He managed with great dexterity and courage to pass through several bodies of the enemy on his route to Poona. At one time, he unexpectedly came on their advance picquet in a nullah, and with singular presence of mind, commenced ringing his horse,

brandishing his spear and proclaiming aloud the titles and valour of the

Peishwa. The picquet of course, taking him for one of their party did not trouble themselves about him,,.. and when he suddenly dashed across the nullah and left them in the greatest surprise and disappointment…’.

The call for help reached Pune, however

before any help could be sent, the Peshwa had heard of General Smith having

reached Chakan, and decided to move his camp towards Jejuri after sending a

part of the force to Wagholi under Naropunt Apte and asking Bapu Gokhale

to stay at the rear and harass Smith thereby delaying his pursuit.

After the Peshwa’s army left and the Arabs withdrew, Staunton gathered his wounded and unit colours and made his retreat to Shirur under cover of darkness on the night of 2nd January.

On 3rd January Mountstuart Elphinstone reached Koregaon and his

journal gives an account of the events as he saw them;

‘The Battalion__ had taken post was hard pressed and lost 2 officers killed (poor young Wingate was one of them) and 3 or 4 wounded out of the 8 _?more___ of the artillery men were killed with many of the sepoys when the whole were saved by the flight of the Peishwa alarmed at the near approach of Gen Smith. This took place yesterday morning after the attack had lasted one afternoon and the whole night. The Peishwa and all his _____ sat on a hill near Phulshahar about two miles off to enjoy the sight of the battle. We …arrived here about one. Immediately went to the village and found some wounded sepoys who could not

be removed for want of carriage. We then entered the village which showed

all signs of violence and havoc, the houses were burned and scattered with

accoutrements and broken arms and the streets were filled with the bodies of

dead men and horses. The men were mostly Arabs and must having attacked

most resolutely to have fallen in such numbers. There were some wounded

likewise which we took care of like our own. I suppose I saw 50 bodies within

the village and half a dozen without, which with the wounded and the dead who

were in places from where they could be carried away would make a great account

not perhaps under 200. About 50 bodies of sepoys were found imperfectly

buried and ____ of Europeans besides the officers (Mr Chisholm’s body without the head). Our great loss was in a sally in which almost every man

was said to have been cut off.’

On 6

January 1818, Elphinstone proceeded to Shirur and after meeting Staunton wrote

what he learnt of the battle,

‘bodies of Arabs coming up the river bed, …got in and after ___ fighting occupied a great part of the village. There was then incessant firing and frequent charges. The Arabs did not ____ well in the latter but were excellent shots

all the artillery men killed were hit on the head. All the men but one gun were killed. Gun taken but__-recovered by a charge. ….Wingate (was) taken in a temple when wounded but released by a charge. Horse charged into the village; but the great damage was done by Arabs in an enclosure which could not be stormed The__ men could not be got to …. The Europeans talked of

surrendering. The native officers behaved very ill and the men latterly could

scarce be got even by kicks and blows to form small parties to defend

themselves. They were ____under ______ thirst fatigue and despondency. ____ that I have seen tried to ?challenge themselves and are surprised to find they only thought to ___ done a great action. Yet an action really greater has seldom been ?achieved’.

The battle at Korgaon influenced Elphinstone profoundly. After his near experience of the battlefield and seeing the injured at Shirur, he was impressed by the perseverance of the entire English force. He also knew that only a small part of the Peshwa’s army participated in this battle and moved away on Gen Smith’s arrival at Chakan. Nevertheless, in June 1818, days after the Peshwa had surrendered, Elphinstone returned to Koregaon and sent a proposal to erect a Victory pillar here to the Governor

General. His decision to choose Koregaon over Khadki or Ashti to establish a

victory pillar seems odd, however, at that time it affirmed to the public -

that this was indeed a triumph of the British rather than what the various

participants seemed to indicate in their letters and reports. The proposal was approved

and when it was erected, it carried names of the killed and some of the wounded

from the British side. It also carried a plaque that declared

‘This Column is erected to commemorate the defence of Corygaum

By a detachment commanded by Captain

Staunton of the

Bombay establishment

Which was surrounded on the 1st of

January 1818

By the Paishwa's whole army under his personal command

And withstood throughout the day a

series of the most

Obstinate and sanguinary assaults of his

best troops

Captain Staunton

Under the most appalling circumstances

Persevered in his desperate resistance

And seconded by the unconquerable spirit

of his detachment

At length achieved the signal

discomfiture of the enemy

And accomplished one of the proudest

triumphs

Of the British army in the East’.

The

soldiers and officers at Koregaon came for special treatment from the British

in the years to come as far as service, pay and promotions were concerned.

Staunton was handsomely rewarded by rapid promotions and a sword of honour. Indian

troops received an extension of service for five years beyond their initial

service period. The gallant defence of Koregaon undoubtedly deserved many

awards; however, it was overstating the case to convert it into a victory. Many of the soldiers in the British ranks were Muslims, there were men from the ‘Mahar’ community, Marathas as well as soldiers from south India. The Maratha army too had an army of many

communities led by the Peshwa. From the British side, a Maratha named Cundojee Mullajee

who was injured in the battle was promoted to Jamadar and appointed as

caretaker of the monument in perpetuity when it was completed in 1824.

The various accounts of the battle testify to the obstinate defence of the British forces over an entire day. With the impending arrival of Gen. Smith’s army, the Peshwa had to resume his running battle while waiting for other Maratha chiefs to join him. Captain Staunton, picking up most of his wounded and hurriedly burying some of the dead, ‘retreated’ to Shirur rather than complete his mission of providing any relief to Pune.

For Elphinstone however, it was the ‘proudest triumph of the British army in the East’. His interpretation of events remains with us to this day.

Eventually,

History is always written by the victors. Thereby hangs a tale.

References

1. Selections

from the Peshwa Daftar volume 41.

2. Elphinstone

journal (India Office) (unpublished).

3. BISM

Quarterly 1939.

4. ‘Corygaum column’ by Wylie (1839).

5. Elphinstone’s Intelligence on the Peshwa (unpublished).

6. Poona

Horse.

7. Bajirao

II and the Downfall of the Maratha Power by SG Vaidya

Author has written ‘Solstice at Panipat’, ‘Bakhar of Panipat’ and ‘The Era of Baji rao’.

To read more articles by Author

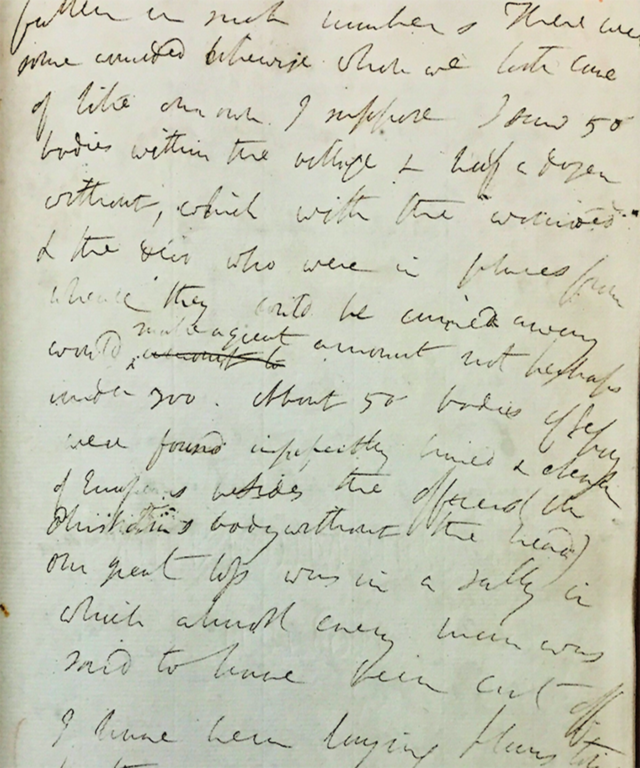

Elphinstone's Journal describing the scene on January 3, 1818.

Elphinstone's Journal describing the scene on January 3, 1818.