- Did Aurangzeb conquer the Deccan or did his desire to defeat the Marathas, for which he shifted to the Deccan, contribute to his downfall. Excerpts from the book.

This is an excerpt

from the author’s soon to be released book ‘Aurangzeb-Whitewashing Tyrant, Distorting

Narrative.’

‘It may be also

asserted that if the monarch (Aurangzeb) maintains his design of becoming

master of all Shivaji’s fortresses, he will need, before he succeeds, to live

for as many years more as he has already lived.’ -Niccolao Manucci.1

Many of the Aurangzeb

hagiographers try to show him as the ‘Conqueror of Deccan.’ The contempt shown

by the Mughal chroniclers to Marathas is also copied almost verbatim when these

critics declare that ‘Marathas can’t stand and fight an open battle.’ A similar

stand is taken by the author in ‘the book,’ which has a severally flawed

narrative from the historical point of view. The Mughal-centric lens had

shielded them from seeing the expansion Maratha Empire had achieved in the

Deccan all the way to Tamil Nadu, even when the Mughal power was at its peak.

The charge of these critics that ‘Marathas were no match for the Mughals in an

open battle’ left us wondering how much Maratha history or military history

they have studied during their research.

Have they not

heard of the famous large-scale battles fought like the Battle of Vani-Dindori

after the second sacking of Surat in 1670? 2

Who has forgotten the famous Battle of Salher (1672), where the Maratha army

under Prataprao Gujar (C-in-C) and Moropant Pingale (Peshwa) decisively

defeated the Mughal army 1.5 times larger in size? 3 This was the bloodiest confrontation fought between Marathas and

Mughals. After this battle, the intensity, scale and frequency of clashes

increased. Battle of Titvala in 1683, Battle of Dodderi, Battle of Basavapattan

(both in 1696) are enough to show that Maratha forces were equal to the task of

taking on Mughal armies in open battle. 4

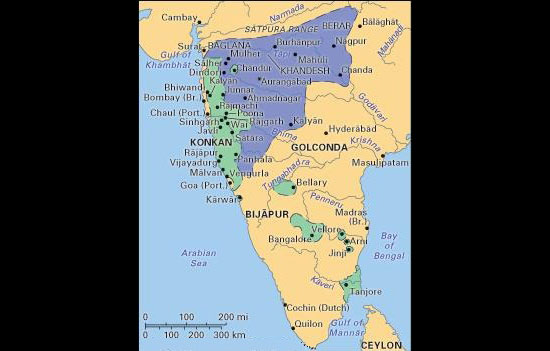

Maratha Empire during Shivaji. Credits Nana Katya.

Maratha Empire during Shivaji. Credits Nana Katya.

The problem here

is not the battles or end results themselves but the mindset of certain

analysts and historians that ‘we can’t call this a legitimate battle unless

both the armies fight on the terms set by us.’ This is most baffling,

considering that why Maratha commanders will fight on terms and conditions of

the Mughal army or by their critics?

The armchair

Napoleons and Caesars who are criticizing the battle tactics must understand

that if Maratha army with minimum resources, less number of casualties (for

both sides), without erecting tower of skulls, are soundly defeating the enemy,

then what is the point in unnecessary comparison? Did these critics seriously

think that the expansion of the Maratha Empire from Attock to Cuttack and from

Tanjavur to Lahore happened by only hit and run raids?

Similarly, the

assertion that the Aurangzeb was a ‘Conqueror of the Deccan’ is based on a very

thin line of evidence. Was Aurangzeb really a ‘Conqueror of Deccan’ or had he

started on the path which ultimately led to the weakening and then the

destruction of the Mughal Empire?

Queen Tarabai Kolhapur.

Queen Tarabai Kolhapur.

Phase Three of the 27 years war in Deccan

“Delhi city is looking very miserable today,

The

condition of the King of Delhi (Aurangzeb) is same,

Like

a fierce goddess Bhadrakali had killed the demons,

Maharani

Tarabai, Wife of Chhatrapati Rajaram, has killed Mughal soldiers.”

-- Kavi Govind

Paramanand (Grandson of Poet Paramanand) 5

By taking refuge

at Ginjee, Chhatrapati Rajaram had forced Aurangzeb to stretch his forces to

the breaking point on the vast fronts from Maharashtra all the way to Tamil

Nadu. After a prolonged siege, finally, Maratha nobles took the decision to

move the centre of gravity back to Maharashtra once again. The siege, which had

dragged on for eight years, had served its purpose. With Mughal reinforcement

moving towards Ginjee; it became increasingly difficult for Zulfiqar Khan also

to justify the delay in capturing it. Finally, he was able to capture the

Ginjee in January 1698, which was renamed Nasaratgad after his title of

‘Nasaratjang’. 6 The fort was

captured only after the Chhatrapati Rajaram and other important Maratha nobles

had already left for Vellore and then onwards to Maharashtra with a three

thousand strong Maratha cavalry escort. 7

The

last gamble

For the past four

years from May 1695 to October 1699, Aurangzeb has encamped at Brahmpuri

(renamed: Islampuri) on the banks of Bhima river, while his armies were

challenged and beaten all across the Southern part of India at various places

with much loss of life, valuable war materials and caused much financial drain

on the treasury. The inordinate time taken by Zulfiqar Khan to capture the fort

and his ultimate failure to capture the Chhatrapati; hints either towards

complacency or most probably duplicity. Mughal chroniclers as well as European

company officials both have noted, either cryptically or openly that the fort

has changed hand due to bribery, and Chhatrapati was able to escape due to the

connivance of Zulfiqar Khan. 8

This has left a

gaping hole in the overall planning of the Aurangzeb. As Chhatrapati himself

entered Maharashtra again, he realized that the war would become intense in the

near future. By this time, he had spent close to 19 years in Deccan but still

failed to subdue the Marathas. His most trusted nobles, including

Ghaziuddin‘Firoz Jung’ and Zulfiqar Khan ‘Nasaratjung,’ were not able to check

the growing Maratha power.

Hence he took a

decision with far-reaching consequences; that is, to start a campaign for the

capture of Maratha forts, with a hope that it would ultimately lead to the

downfall of the Maratha Empire. So on 19th October 1699, Aurangzeb

opened a campaign under his personal command against Maratha Empire. Saqi

Mustaid Khan quoted Aurangzeb’s words while opening the campaign against

Marathas as ‘My object in this journey is

nothing except holy war’. 9

The theme of holy

war here is not an isolated occurrence, but the same has been reported in

various akhbars & contemporary letters, which confirm that this was no

figment of imagination of later chroniclers. The first mention of ‘holy war’ in documents can be found in the

complaint letter dated 2nd November 1699, with the confiscation of

arms from representatives of Hindu nobles in Mughal camp. 10 This practice had been stopped only after a petition reached

Aurangzeb himself; as these Hindus were paying Jiziya and are fighting in ‘Holy

war’ for the Mughal government against Marathas. Consider some of the other

akhbar with the same theme given below;

Tarabai Palace inside Panhala Fort, now a government office.

Tarabai Palace inside Panhala Fort, now a government office.

In the year 1700,

Sayyad Mazali, the brother of Gulbarga’s Qazi Abdullah has came to Emperor’s

camp (near Panhala) with fifty horsemen and fifty foot-soldiers. Through Yar

Ali Beg, he met the Emperor (Aurangzeb). Following gifts were given to him,

five hundred gold mohur, a sword, and two quivers. Sayyad Mazali requested that

he and his personnel had come to wage ‘holy war’ here. Aurangzeb exclaimed that

‘by God’s grace, I will kill the unbelievers with the stroke of my sword’.11

Similarly, Abul

Rasul from Akbarabad (Agra) wrote to Siyadat Khan that he is ready to come to

Deccan to fight in a holy war. ‘If the Emperor orders, I will come and fight in

Deccan’. 12 The fort commander of

Shivneri, Nasirullah Khan, has written to Aurangzeb, ‘as you have declared the

holy war against non-believers, I want to participate in this war. If you

permit, I will keep my deputy Sheikh Hussain here and will join you with 500 of

my best troops.’ Aurangzeb was very pleased and ordered him to ‘come at once. 13

Since ‘the author’

has completely ignored the words and the subsequent acts of Aurangzeb, which

mention his focus on ‘holy war,’ the critical analysis of this phase is totally

absent from the narrative. So like Aurangzeb roamed Maharashtra aimlessly,

laying sieges and taking the forts in the vain hope of subduing the Marathas,

even ‘the author’ is roaming aimlessly in the wilderness of the questions for

justifying the actions of Aurangzeb from 1699 till his death in 1707.

The peace terms

offered by Maharani Tarabai after the death of Chhatrapati Rajaram were

rejected brusquely in July 1700 by the Aurangzeb. In fact, the death of

Chhatrapati gave further hope to him that if given a strong push, the collapse

of the Maratha Empire is imminent. Hence he ordered fresh reinforcements.

Table

19.1: Reinforcements called by Aurangzeb to Deccan in 1700 for final push against Marathas. 14

|

No

|

Province

|

Governor

|

Nature

of reinforcements

|

|

1

|

Kabul

|

Prince Muazzam

|

2000 musketeers,

2500 horses & 500 camels

|

|

2

|

Ahmadabad

|

Shujaet Khan

|

1000 horsemen

|

|

3

|

Ajmer

|

Sayyad Khan

|

1000 horsemen

|

|

4

|

Malwa

|

Mukhtar Khan

|

1000 horsemen

|

|

5

|

Gwalior

|

Jan Nisar Khan

|

1000 horsemen

|

|

6

|

Agra

|

Itikad Khan

|

1000 horsemen

|

|

7

|

Itawa

|

Khairandesh Khan

|

1000 horsemen

|

|

8

|

Awadh

|

Zabardast Khan

|

500 horsemen

|

|

9

|

Burhanpur

|

Muhammad Kambu

|

500 infantry

|

|

10

|

Allahabad

|

Siphadar Khan

|

1000 musketeers

|

Every Governor was

supposed to pay the salary in advance as well as to give up to Rs. 20,000 to

the units coming to Deccan for their upkeep along with their weapons and

horses. But till October 1700, no reinforcements came from Ahmadabad; hence

Aurangzeb reduced the ranks of all major officers posted there.15 In-fact, Shujaet Khan from Ahmadabad

has informed that the number of soldiers ready to serve in the Deccan war is

very less; hence he is planning to send three lakhs for the imperial treasury

in place of the soldiers. Aurangzeb sent a harsh reprimand to Shujaet Khan; ‘I am waging the holy war for the

destruction of evil unbelievers, and for that, I am constantly taking strenuous

efforts. You need to help an Islamic King in this with your soldiers’.16 The reprimand had the desired effect

on Khan and by the end of December 1700, he sent his son Najar Ali to fight

against Marathas.17 Now a military

commander whose army’s pay has been in arrears from six months to more than a

year must have jumped on such an offer, but Aurangzeb’s rebuke to Shujaet Khan

shows how serious he was regarding the war till the bitter end.

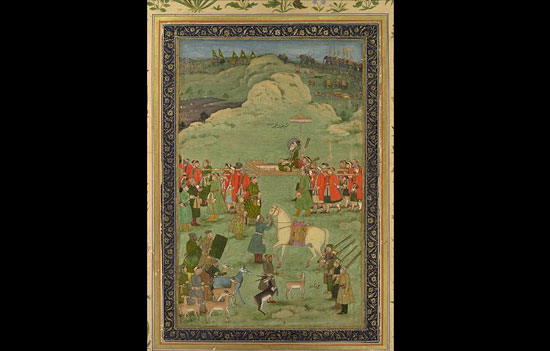

Aurangzeb hunting. Courtesy Khalili Collection of Islamic Art.

Aurangzeb hunting. Courtesy Khalili Collection of Islamic Art.

Whereas Muhammad

Murad Khan (the patron of Khafi Khan) has written from Godhra that ‘when you, my lord are waging holy war

against unbelievers and here I am enjoying my life is not acceptable to my

conscience. Hence, sire, if you order me, I will keep my deputy at Godhra and

come to your camp to wage the holy war along with you. Even if I get a

miniscule part of your righteous war, I will be much happy in life and after’.18

He reached at the time siege of Panhalgad in early 1701.19

The musketeers

sent by the governor of Allahabad also reached in January 1701 to Aurangzeb’s

camp. Muhammad Saleh, the son of Itikad Khan (Governor of Agra), reached

Aurangzeb’s camp with his unit in February 1701.20

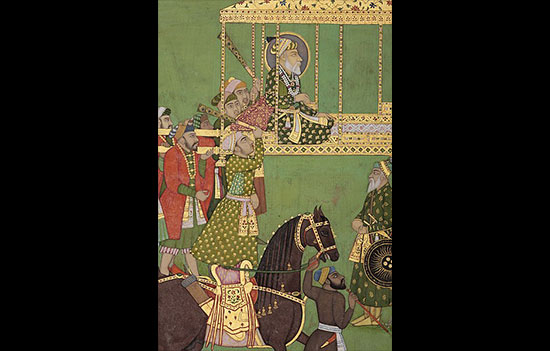

Aurangzeb on a

palanquin. Courtesy Bhavanidas.

Aurangzeb on a

palanquin. Courtesy Bhavanidas.

As Aurangzeb took

the personal command for the sieges of the Maratha forts, he forgot the key

principle of delegation and not to micro-manage everything. Earlier, the will

of the Emperor was supreme for even routine things, but with this decision, the

micromanaging reached its peak. The camp of Aurangzeb was not only military but

also contained all his administrative departments. But when he focused

everything on sieges and battles instead of planning strategy, then running

administration of the Mughal Empire naturally took a backseat.

The stage has now been

set for the final showdown between Mughal and Maratha Empires.

To read more buy

book, click HERE

About Author: Saurabh is an avid reader and keen researcher,

especially in the history of Maratha Empire. This is an excerpt from his soon to be

launched book which is being published by Evincepub Publishing.

About the Book: It is a combination of meticulous research with a lucid plot. The current narrative which is getting built around him like, ‘much misunderstood king’ and ‘protector of temples’ has prompted the author to look for historical accuracy of this new portrayal. Who he really was? As described by his court records and contemporary chronicles or as reinterpreted by modern historians?

This book is an

attempt in fact finding where the author tries to critically examine the life

of Aurangzeb with contemporary records. Today when the debate is raging

passionately across academic circles and on social media platforms, this work

has become all the more relevant and essential.

Also read

1. Battle

of Salher

2. Maratha

rule in Thanjavur

3. Return

of Queen Yesubai

4. How

the Marathas captured Attock in modern day Pakistan

5. Album

Panhala Fort

References

1. N.Manucci, Storia do Mogor -Volume-III, Tr-W.

Irvine, Pg-306, 1907.

2. K.A.Sabhasad, Sabhasad Bakhar, Tr-S. Sen Pg-87-88.

1920.

3. Ibid,

Pg-103-04.

4. J.Sarkar, History of Aurangzib-Volume- IV. Titvala:

Pg-303-04, 1930. &

S.M. Khan, Maasir-i-Alamgiri, Tr-J. Sarkar, Dodderi: F-376-78, Pg-228-

29, Basavpattan:

F-379, Pg-230. 1947.

5. G.S.Sardesai,

Aitihasik Patrabodh, Pg-24, 1952.

6.

C.S.Srinivasachari, History of Gingee and

its Rulers, Pg-338. 1943.

7. Ibid, Pg-336.

8. Ibid, Pg-338

& 347.

9. S.M.Khan, Maasir-i-Alamgiri, Tr-J. Sarkar. F-410,

Pg-249, 1947.

10. S.M.Pagadi, Mogal Darbarachi Batamipatre-Volume-1, O

Pg- 260. 1978.

11. Ibid, O

Pg-305.

12. Ibid, O

Pg-317.

13. Ibid, O Pg-

359.

14. Ibid, O Pg-

396, 397, 399, & S.M.Pagadi, Mogal

Darbarachi Batamipatre-

Volume-2, O Pg-53, 1983.

15. S.M.Pagadi, Mogal Darbarachi Batamipatre-Volume-1, O

Pg-427, 1978.

16. S.M.Pagadi, Mogal Darbarachi Batamipatre-Volume-2, Preface-

O Pg-36.

1983.

17. Ibid, O Pg-53

& 99.

18. Ibid, Preface

O-Pg-36.

19. Ibid, O Pg-90.

20. Ibid, O Pg-68.