Chapter 2 highlights select women characters from the Mahabharata.

Satyavati

At

the very essence of the Mahabharata is a political drama, and in this story, one

can consider Satyavati to be one of the most politically shrewd and astute of

all.

Today, not many modern readers recognise Satyavati as a powerful character, much less an influential one. But there are many aspects to her journey from Matsyagandha, a fisherman’s daughter to Satyavati, the queen of Hastinapur. Satyavati was a woman who made her way to the top of the ladder, slowly but steadily, by fully utilising her presence of mind and her penchant for promises and politics.

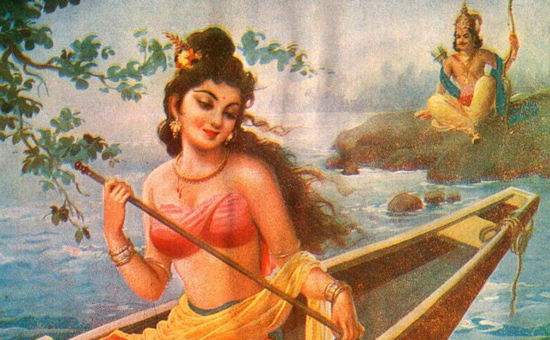

Satyavati was the daughter of the Chedi king, Uparichara Vasu and Adrika, an apsara cursed to be a fish. She was adopted by the tribal fisherman chieftain, Dusharaj, and earned the name Matsyagandha (literally meaning ‘she who smells like fish’), while helping her father with his job as a ferryman.

Once,

while ferrying Rishi Parashara across the Yamuna, he explains that she is meant

to have for her son one of the greatest rishis of all time with him. Thus,

Satyavati was the mother of Veda Vyasa, who would later go on to write the

Mahabharata. Satyavati was also blessed by Rishi Parashara to never have the

aroma of fish lingering around her and to instead be associated with the smell

of flowers, thus earning her the name Yojanagandha.

Satyavati, much like Kaikeyi, is a very interesting character to study due to her multifaceted nature. She is also said to have been unapologetically blunt and honest, but also gentle and kind. Satyavati was never afraid of bending the rules and, if need be, didn’t shy away from making her own rules.

When

Shantanu sees Satyavati, many years after Ganga (his first wife) and Devavrata (his son)

left him, he is immediately smitten and asks for her hand in marriage. However,

Satyavati lays down the condition that her son, not Devavrata (who had returned), would be king, denying the latter his birthright for her benefit. When Satyavati’s father contends that Devavrata’s children may challenge her grandchildren or children’s rights to the throne, Devavrata takes an oath to never marry, thus earning him the name Bhishma.

Satyavati had two sons with Shantanu, Chitrangada and Vichitraveerya who

married Ambika and Ambalika, sisters of Amba, who upon being rejected by

Bhishma due to his vow to never marry, became Shikhandi, the first ever

transgender entity in the epics.

However, both Chitrangada and Vichitraveerya met tragic ends before any heirs are born, with the former being slain by a Gandharva and the latter dying of a disease. Thus, Satyavati’s plan for her children to ascend to the throne had seen a depressing end. Unrelenting, Satyavati called for her first son, Veda Vyasa, who had given her the boon that he would appear before her whenever she thought of him.

She asked for Veda Vyasa to meet Ambika and Ambalika and bear heirs through niyoga, in which a holy person helps continue a lineage. It is famously said that due to Veda Vyasa’s abnormal appearance, Ambika closed her eyes when she met him, thus resulting in Dhritarashtra, her son, being born blind and that Ambalika turned extremely pale and began shivering when she set eyes on him, and as a result, Pandu, her son, was born sickly and pale. 5 (Yayavaram, Krishnamurthy - Speaking

Tree: The Story of Satyavati, speakingtree.in)

Dhritarashtra and Pandu became the fathers of the Kauravas and Pandavas, respectively. Thus, without Satyavati, the Kuru dynasty may have seen a premature end and it is because of her that it retained its longevity. After Pandu died, Satyavati found the grief caused by her grandson’s death unbearable, and upon being warned by Vyasa that the destruction of the rest of the Kuru clan would be much more unendurable for her, she retreated to the woods with her daughters-in-law, Ambika and Ambalika, where she lived during her last days.

Satyavati

is a conflict of good and evil as a person. She has been praised for her

shrewdness, her presence of mind, her farsightedness and her mastery of

realpolitik, which is politics or diplomacy based on practicality and

circumstance rather than ideologies.

However,

she has also been criticised for her blind ambition and her unscrupulous ways

of reaching her goals. Satyavati is one of the few unconventional female

characters in the Mahabharata, but all the more influential.

Uloopi

Draupadi is widely and popularly recognised as Arjuna’s wife, and yet, in the constant race to understand her as the complex character she was, we often forget the women who stood by Arjuna even in his darkest of times. He had four wives - Draupadi, Uloopi, Chitrangada and Subhadra, but only one of them had ever saved his life.

As Draupadi was married to all five of the Pandava brothers, there was a fair split of Draupadi’s time with each brother that had been decided upon. She would spend one year as the wife of each brother, and during each year, only the designated brother could meet Draupadi, barring anyone from entering his chamber. 6 Anaadi Foundation -

Arjuna and Ulupi: Mahabharata Katha, anaadifoundation.org)

However, one day, during Yudhishthira’s year with Draupadi, a few distressed Brahmanas came up to Arjuna, lamenting that their cows had been stolen yet Arjuna’s weapons were in Yudhishthira’s chamber. Unwilling to break his Kshatriya dharma, he quietly stole into the room and took his weapons. Later, although Yudhishthira said that Arjuna was forgiven, he adhered to the consequence of his rule-breaking and set out on an exile of twelve years.

Uloopi was the Naga princess and daughter of the powerful Naga king, Kauravya. While on his exile, Arjuna was doing tapas in the Ganges, when Uloopi, completely enamoured by him, pulled him into the water and to the underwater Naga kingdom. It is because of Uloopi’s blessing that Arjuna is the only Pandava prince who can breathe underwater and understand the language of marine animals. 7

(Bapat, Rohit - Least Known Character of the Mahabharata: Uloopi, robasword.com )

She

pleaded with him to marry her and Arjuna, also smitten by her beauty, agreed.

Uloopi also had a son with Arjuna called Iravan, who later on, according to South Indian folklore, agreed to sacrifice himself for the sake of the Pandavas’ victory in the Kurukshetra War. After much time together, Arjuna decided to move on with his pilgrimage exile and left Uloopi behind in the Naga kingdom.

On

his way to the east, Arjuna passed through Manipur and marries the princess of

Manipur, Chitrangada, with whom he has a son called Bhabruvahana. Arjuna forgot all about Uloopi in due course, while

Uloopi still longed to see him, even after realising that he no longer

remembered her. At the end of his 12 year exile, Arjuna left Chitrangada and

Bhabruvahana with the promise of visiting and headed back to his brothers. 8 (Amar Chitra Katha: Uloopi)

Instead of directly approaching Arjuna, Uloopi saw that he loved Bhabruvahana very much and so, decided to devote her time and love to the latter and see that he grew up to be a worthy successor of his maternal grandfather, the king of Manipur, as well as a son as commendable as his father. Uloopi and Chitrangada developed a close bond in the years of Arjuna’s absence and Uloopi contributed majorly to Bhabruvahana’s upbringing. Being a powerful Naga princess, she was well-versed in warfare and military arts, the knowledge of which she passed on to him, and told him about the many feats of bravery Arjuna had achieved, constantly reminding him of what he would have to live up to, which, much to her satisfaction and pride, he eventually did.

It

was during the Kurukshetra war that Uloopi played her biggest role yet.

Arjuna had just defeated Bhishma on the battlefield, and the latter’s brothers, the Vasus who were watching from the heavens, were extremely upset that their brother had been killed on unfair terms. So, they approached their mother, Ganga and asked her to curse Arjuna, so he would go to hell when he died.

Uloopi,

upon stealthily overhearing this deadly conversation, is extremely perturbed,

and begs the Vasus to lift the curse. Moved by her pleas, the Vasus admit that

they cannot completely take the curse back but they can alter it, saying that

if Arjuna is killed by his own son in battle, the curse would be nullified.

Uloopi was shaken when she heard this but agreed, showing her diplomacy and

composure.

Bhabruvahana had ascended to the throne of Manipur after his grandfather’s death and upon hearing that his father, Arjuna, would be passing through his kingdom as the guard of Yudhisthira’s Ashwamedha yagna horse, prepared to welcome Arjuna with open arms. Arjuna, however, was disappointed as he had hoped that his son would challenge him to a duel.

In

a dilemma, torn between the idea of pleasing his father and the idea of

fighting his father, Bhabruvahana approached Uloopi for advice, who counselled

him to go ahead and fight his father. In an epic clash and a mad rage of

blinding fury, Bhabruvahana managed to kill his father and out of grief and

exhaustion, swooned on the battlefield.

Chitrangada

arrived at the scene, distraught, and pleaded with Uloopi to bring Arjuna back

to life with her divine powers. Uloopi remained unmoved as both Chitrangada and

Bhabruvahana hurled abuse at her in fits of fury before vowing to join Arjuna

in death if she did not resurrect him.

Finally,

Uloopi summoned the sacred gem of the Nagas which had the power to bring the

dead back to life and used it to breathe new life into her dead husband.

Arjuna, as if reawakened from a deep slumber, saw Uloopi and finally remembered

and thanked her with gratitude that had been due for years now.

Thus, Uloopi saved Arjuna’s life, raised two of his sons to be excellent princes and kings and bestowed him with powers underwater.

If there is one common theme in Uloopi’s story, it is selflessness.

What started out as an act of self-indulgence turned into a life of selflessness. Instead of retreating into a shell of self-pity when Arjuna left and forgot about her, she remained the same mysterious, fiery young princess, just with a new air of understanding and maturity. In Chitrangada, she could have seen competition for Arjuna’s affection or the reason Arjuna left her, but instead she chose to see her as a sister and even nurtured a genuine bond with her. Bhabruvahana was not her own, and she still treated him no different from her treatment of Iravan.

Uloopi

saved Arjuna from suffering and death, raised Bhabruvahana in a way that he

perhaps never felt the absence of his father and never expected gratitude or

anything in return.

Altruism out of love and devotion seems to be an

intricacy in the larger-than-life stories of women like Mandodari, Tara and, of

course, Uloopi and yet, this defining trait shaped them to be the strongest of

female characters in both epics.

Kunti

Kunti

was born as the feisty young Pritha, daughter of King Surasena who gave her to

his childless cousin King Kuntibhoja who raised her with much more affection

than her biological father ever had. Perhaps this first parental transfer

hardened Pritha to the ways of the world, as she was handed off by her own

father without a second thought. Kunti was one of the two most powerful

matriarchs in the Mahabharata purana. 9

(Kumar, Manisha - The Two Matriarchs of the Mahabharata: Kunti and Gandhari, dollsofindia.com)

She

was many things in her lifetime and even afterwards: One of the Panchakanyas, a

princess, a queen, a wife, a mother, a stigmatised woman and much more. Kunti

was a very complex character as she had two opposing sides to her persona that

makes readers respect and despise her at the same time. She was always

portrayed as a righteous and noble woman but also as a heartless mother who

left her own son to die and never accepted him until it benefitted her.

One

wonders why Kunti did what she did, what might have been running in her head

when she made some of the political and personal moves she did and most of all,

how a story can be so enveloped in fortitude and cruelty all at once.

As a young girl, Kunti was a favourite of the famed Rishi Durvasa, as she always tended to his needs and served him with a pure heart whenever he graced Kuntibhoja’s kingdom. Pleased by her indomitable spirit and gracious service, he gave her a mantra which when said would invoke a god of his choice along with a son.

Abiding

by her curious nature, Kunti, then Pritha, decided to test the mantra and, much

to her delight and alarm, Surya, the Sun god, appeared before her with a son

for her to take care of, none other than Karna.

Kunti

dreaded the thought of the tainted reputation that came with a child out of wedlock

and made the heartbreaking yet courageous decision to set her newborn afloat in

the river, thus burying a chapter of her life where she hoped no one would find

him.

Kunti chose to marry Prince Pandu of Hastinapur in an

organised swayamvara, which is evidence that women, or at least women of

royalty, had the right to choose their own spouse. 10 (Vaideshwaran, Sanjanaa - Contribution of Ancient Indian

Literature to International Law)

A

little later, Pandu married Madri, the princess of Madra, which initially may

not have gone down well with Kunti but there are accounts of the two co-wives

growing closer than sisters over time. Perhaps, this bond was why when Madri

committed sati, she took care of Nakula and Sahadeva like her own.

Due to a curse that stipulated that Pandu would die the moment he touched a woman, neither Kunti nor Madri could bear him a child, and so with much reluctance from Kunti’s side, Pandu persuaded her to invoke children with the mantra that Rishi Duravasa had given.

Kunti invoked Dharmaraj, the god of death for Yudhisthira, Vayu, the god of the winds for Bheema and Indra, the god of the heavens for Arjuna. However, Kunti refused to invoke a fourth child even upon Pandu’s pleading and instead, to appease her husband, shared the mantra with Madri, who invoked the Ashwini twins for Nakula and Sahadeva.

Both

Pandu and Madri died soon after the Pandavas were born and Kunti, despite being

given the option of sati, made the brave decision to singlehandedly raise the

five boys. This is evidence that the idea of single parents, especially single

mothers, was not looked down upon even back then.

Back

in Hastinapur, Kunti, although a dowager queen, ensured that her sons were

treated with no less respect and received the right education throughout their

youth. This period was a bittersweet one for Kunti, as she had the love and

support of Bhishma, Vidura and other elders but also had to watch her sons

constantly clash with the bullying Kauravas. Her silent strength, determination

and maturity at a young age are the most prominent at this stage of her life.

Indirectly, Kunti also decided what Draupadi’s life would be like the moment she was married. Arjuna had won Draupadi at her swayamvara and all five Pandava brothers had escorted her home. When they gleefully called out to their mother, asking her to see what they brought home, she unsuspectingly told them to divide it among themselves, while still inside. It was only when she came outside that she realised her mistake, but it was too late by then, the brothers, having always obeyed their mother’s orders, all married Draupadi.

There

are two views to this defining episode of the Mahabharata. Some condemn Kunti

for not apologising and thereby, sealing a young bride to such a fate and

others view it as a shrewd move and a way to ensure that the brothers are bound

together for life.

There is not much description of Kunti’s relationship with her daughter-in-law, Draupadi, but from what we know, there was initially much awkwardness in the bond 11

(Kumar, Manisha - The Two Matriarchs of the Mahabharata: Kunti and Gandhari, dollsofindia.com) as it was because of Kunti that Draupadi had ended up not as Arjuna’s wife, which was what she had wanted, but as the wife of five men, which had made her vulnerable to a lot of condemnation throughout her life.

However,

it is also said that Kunti was much aggrieved after Draupadi was assaulted in

court and that she criticized her sons for not doing anything to protect her.

Kunti also proved her political shrewdness and her ability to manipulate a situation on the night before the Kurukshetra war began. Out of fear of self-deprecation, Kunti had refused to reveal Karna’s true identity to the world when it was all he really ever wanted. She hid his lineage for selfish but relatable reasons, but in hindsight, her reluctance might have destroyed Karna from the inside which is what could have turned him into an arrogant young man in search of vindication and not a bestowed title (Duryodhana crowned him King of Anga), as he is reported to have been.

However,

on the night before the war, she used her secret as her only weapon and struck

Karna with it, by showing that she was willing to sacrifice her firstborn for

her other five sons. Kunti approached the Kaurava tent where Karna was and

divulged the secret of his birth to him, in the process, hoping to extract the

promise that he would spare the lives of the Pandavas. Karna agrees but vows

that he will not reprieve Arjuna for the insults the latter has taunted him

with.

Kunti was yet another intricate persona. Kunti was every bit the devoted and affectionate mother but neglected her firstborn when he needed her most. She showed that she was benevolent and compassionate when she treated Madri like a sister and her children as her own but also demonstrates that her ambition for her sons blinded her when she refused to revoke her words on the ‘splitting’ of Draupadi just so her sons wouldn’t quarrel.

Thus,

one can say that her transformation from the feisty, wild-spirited Pritha to

the mature and wise Kunti, ensured her remembrance as the ultimate matriarch.

Hidimbi

Hidimbi

is very much the forgotten queen of the Mahabharata.

There are many misconceptions regarding the Mahabharata and each individual’s story but perhaps, one of the biggest fallacies yet is the belief that Draupadi was the first woman to marry a Pandava prince. Hidimbi has always been an integral part of the purana, whether she has received her due credit or not. She was the true feminist figure of her times and has always been a paragon of modern thinking.

Hidimbi

was a rakshasi and the sister of Hidimba, a rakshasa who terrorised the local

villagers, killed them and stole their livestock. Hidimbi, however, was always

kind-hearted and as much as she loved her brother, she hated living under his

thumb and disapproved of his cruel methods.

While

the Pandavas were on their exile, they stopped to rest in the forest that

Hidimba had monopoly over. One of the days in the forest, Bhima had found a

lake and was about to take a sip of water when Hidimba emerged out of nowhere

and claiming that Bhima was stealing his water, proceeded to engage in a brawl.

Bhima is triumphant and kills Hidimba.

Upon seeing her brother’s death, Hidimbi asked Bhima to marry her and after Kunti’s consent, the two were married. This makes Hidimbi the first daughter-in-law of the royal empire and the first wife of a Pandava brother who never got the veneration she deserved in our cultural history.

Hidimbi

and Bhima had a son called Ghatothkacha together

who would later be instrumental in the Kurukshetra war. After Ghatothkacha was

born, Bhima, his brothers and Kunti left the forest and although Hidimbi and

Bhima each tried to convince each other to follow the other, Bhima ultimately

decided that his brothers would need him in the impending Pandava-Kaurava

conflict and Hidimbi did not have the heart to leave the forest, her home.

Hidimbi has been an unrecognised role model for many generations and the values of her story are still relevant in today’s modern world. Bhima and Hidimbi’s story is an unconventional one that defies norms as a marriage between a prince, especially from the celebrated Kuru clan, and a rakshasi in the forest was definitely not common. 12 (Coomar, Debolina - The Mahabharata’s Bhima may have married the most modern woman ever, huffingtonpost.in)

In

some way, this also sets a tone for inter-race, inter-cultural and other

socially frowned upon marriages and propagates the message that love does not

follow convention.

Hidimbi was a single mother, much like Kunti, who independently raised her son, after losing all support that she had in her life as her brother was killed and Bhima had left. Hers is a tale of sacrifice, belief, love and mutual understanding. Hidimbi also subtly demonstrates the art of letting go in any kind of relationship, which is a valuable lesson in today’s times.

Draupadi

Draupadi has always been portrayed as the vengeful, powerful, controversial heroine who never shied away from speaking up about the injustices she faced. As opposed to stoic and composed Sita, we see the raging fire in her, unsurprisingly, as she was born of fire. Draupadi always craved to avenge the wrongs done to her and didn’t hesitate from going to lengthy means to do so.

Draupadi

was the princess of Panchal, hence earning her the name Panchali, daughter of

King Drupada and sister of Dhrishtadyumna, a fierce warrior much like herself.

She was a product of hate and the thirst for revenge.

Her

father invoked her for the sole purpose of marrying Arjuna while her brother

was invoked for the destruction of the Kuru clan. Thus, she was a multi-faceted

personality.

However,

few know that Draupadi was extremely well-educated, a scholarly individual and

actually served as the financial advisor of her father until she was married,

all of which add to her image of street-smartness and shrewdness.

Born

as a young woman, she was deprived of conventional parental love and affection

and a carefree childhood, or any childhood at all. 13 (Pattanaik, Devdutt - Sita versus Draupadi, devdutt.com)

A

queen is meant to symbolise the power and prosperity of a kingdom. Therefore,

Draupadi was Indraprastha. As Yuddhisthira gambled away Indraprastha, he had

already lost Draupadi.

Tradition

says that Draupadi married five men as a result of a boon she received in her

previous birth. In a prior form, she had asked Shiva, the god of destruction of

evil, to grant her the boon of marrying a perfect man i.e. one with all five qualities

that make a man equivalent to Indra. As no such man existed, Shiva, as an

alternative, gave her five men who together, were the perfect man.

Krishna came into the lives of the Pandavas as a major guiding force only after they married Draupadi. Draupadi was a creation of circumstance, a fruit of her father’s hatred and a victim of unruly morals of the Kauravas, having borne the ruthless injustice of being assaulted in court and the disappointment and anguish when not one of her five husbands stepped up to save her.

It was this incident that was, perhaps, the final shaping of Draupadi as a person. She realised that she would have to fend for herself and that not even one of her husbands could be trusted to protect her. It was such a disillusionment that could have made her so hard-hearted when it came to seeing her ambitions and goals fulfilled. Draupadi’s assault sealed the fate of both Dusshasana and Duryodhana in one go.

One

can argue that Draupadi was indirectly one of the main causes of the Kurukshetra

War and it is true that her ruthless thirst for vengeance instigated the final

war. However, it is undoubted that Draupadi remains one of the most influential

and powerful heroines in not just Indian, but world history.

Conclusion

It

is evident that all these women were ahead of their time in some way or

another, be it their presence of mind or their ability to endure and sacrifice.

There are multiple common themes throughout all their stories, including

determination, patience, compassion and acceptance.

These characters blatantly flouted the idea of women being quiet and silently suffering individuals, and whether they broke conventions or conformed to them, they left a lasting impact in both their own and others’ stories.

The

epics also show that laws against discrimination, self-defense and other major

topics of debate and discussion in world organizations, like CEDAW, today, were

implemented and followed even in their times. 14 (Vaideshwaran, Sanjanaa - Contribution of Ancient Indian

Literature to International Law)

Sita

skillfully demonstrates the art of self-dependence coupled with independence as

she chooses to be beside Rama, not behind him, when she accompanies him to the

forest. This is yet another example of women of those times constantly and

repeatedly demonstrating their ability to care of themselves and not depend on

a male crutch or any other sort of protector.

This

paper is meant to spread the message that women are fit for so much more than

just sacrifice and quiet endurance, and that they were intellectuals who were

never denied education even back then, that they were warriors who were not

discriminated against on the battlefield and that they carried profound wisdom

and wit even in those times.

To read more articles on Indian Women