Our introduction to traditional grains began with

the Save our Rice Campaign that I was involved in. As part of the Campaign,

we were visiting farmers’ farms, meeting and motivating farmers to

conserve traditional paddy varieties, organising seed and rice festivals, and

developing rice diversity blocks. It is as part of the campaign

that I took home the first traditional rice variety, knowing its

name, knowing where it was cultivated it and who farmed it, knowing the

provenance of my food. It was Gandhasaale, an aromatic rice variety, growing in the Western

Ghats, it has a heavenly fragrance that slowly spreads around the

house when the rice starts cooking in the pot. An

interesting story that the farmer told me is that the variety has

fragrance only when it is grown at an altitude and gets low

night temperatures. They discovered it, he said, when a farmer grew it in the

plains and found that the rice had no aroma.

Since the start of the Green Revolution in the 1960s,

its single point agenda of increasing yield of paddy became the

mantra for the agriculture departments/universities in the country. As a

result, traditional varieties have been slowly dying out. When farmers got

seeds from the market, initially really cheap or even free, they stopped saving

seeds. Some committed farmers continued saving and using their traditional

varieties but by the early 2000s most farmers had given up on the traditional

varieties. Over the years, we began losing the thousands

of varieties of land races that were part of our food and agricultural heritage.

A sample of Rice Diversity. (Credit-Bio Basics)

A sample of Rice Diversity. (Credit-Bio Basics)

At the

same time processed food, with different kinds of food items made with a small

range of grains, have given us the false notion of variety in food. We began

mistaking variety for diversity. Today we have given up diversity and embraced

variety. So we grow and eat less diverse grains, foods and also eat

more non local food, more processed and less whole food, impacting our health

and environmental wellbeing.

The Traditional Rice Varieties

Traditionally,

every variety of rice has had an agricultural and food significance. Some

varieties are suited to certain soils, others require lower night temperatures

or can withstand drought and/or flood, while some others are salinity tolerant. Many

grew tall providing enough hay for fodder and roofing, whereas some had

awn protecting the grain from birds (especially in the aromatic varieties where

the birds are attracted by the aroma that begins right in the field), some were

short season, suitable for the summer rains, whereas others matured slowly

taking all of 180 days. The particularities are endless. Rare scientists

like Dr. R.H. Richharia have documented tens of thousands

of land races and their properties and spent years studying these

varieties.

The

particularities of the varieties do not end with the paddy plants, duration,

seasonality, etc. The grains also have their

unique features. They have specific nutritive,

cooking and eating qualities. Also traditionally specific rice varieties

were used for specific purposes. Every culture had its list of rice for

specific seasons and purposes, which were dependant on the growing season, climate,

cultural observances (which, again, like harvest festivals, were linked to the

agricultural calendar).

The

agricultural families ate the rice they grew. It was converted to parboiled rice in their own yards and either hand pounded or milled and eaten. There were special rices for making tiffin items, those that were preferred for table rice, separate ones for making flattened rice and puffed rice. Aromatic rices had their exalted place, preferred by the royal families. The rices with medicinal properties were another precious bunch. However as one rice expert said, "What medicinal rices? Every traditional variety has some nutritive

or medicinal property. We just need to know it."

Sundararaman Iyer, an organic farming guru from Tamil Nadu says, "The greater the varieties of rice you eat the less you are likely to experience micro-nutrient deficiencies.” Today unfortunately, we have narrowed our choices to a handful of varieties and consume them polished

devoid of fibre and minerals. We, instead, eat a range of processed

foods made with the same grains and mistake variety for diversity. However, it

is diversity that will give us a range of nutritional elements – apart from

fulfilling our need for varied taste. Each of the different rices have their particular

taste profile, and often, most people develop their personal favourites.

In Kerala,

the parboiled red rice was preferred for table rice

with varieties ranging from Thondi

and Paal Thondi from Wayanad, to Kuruva, Chitteni and Chettadi from Thrissur and Palakkad. Each

region had its own specialities. In Palakkad, a variety Thavala Kannan, was cultivated mainly to make aval (flattened rice

or Poha) for offering at the Devi temple.

RiceDiversityBlock at Panavelly Agri-ecology Centre,Wananad(Credit-Save our Rice Campaign)

RiceDiversityBlock at Panavelly Agri-ecology Centre,Wananad(Credit-Save our Rice Campaign)

Each

region had hundreds of varieties. The Save Our Rice Campaign alone

conserves over 250 varieties in Wayanad, over 700 varieties (from all over) in

Karnataka, over 140 varieties in Tamil Nadu and hundreds of varieties in

Chhattisgarh/Jharkhand and West Bengal. Of these, most varieties are conserved

as an end in itself, and about twenty to forty varieties are grown in large

quantities to be consumed as rice.

What we have

come to realise is that the enthusiasm that the farmers have to try out and improve

these varieties is unfortunately not matched by willingness of consumers to try

out these diverse varieties. This is due to various reasons. It ranges from

lack of time and attention to focus on cooking in the house to reluctance to

try something new (the irony, however, is that urban consumers are trying newer

cuisines everyday) to something trivial like these varieties take longer

to chew and eat! Most traditional varieties also take

longer to cook, as most are made available with bran. But we overlook the fact that this is what enhances the

nutritional profile of these rices!

For

example, in Tamil Nadu, Mappilai Samba, a traditional rice variety that had almost slipped into oblivion is now

gaining popularity. It is known for its strength giving properties. It got its

name from having been fed to potential bridegrooms so that they could pass the

test of strength to win the bride. Today this rice in its unpolished form is

becoming popular for health reasons and also because it has relatively lower glycaemic

index. Since it takes long to cook, many prefer to use the red rice as flour to prepare popular South Indian snacks

like puttu, kozhukattai and adai with the Mappilai

Samba rice. Similarly the Poha (flattened rice) and puffed rice (pori/kurmura) made with Mappilai Samba are superlative. Not only

can they can be used to make typical South Indian snacks; you can eat it as is or

even make Bhel or Muesli. Such versatility!

Mappilai Samba Puffed Rice in use for making Bhel (Credit-Bio Basics)

Mappilai Samba Puffed Rice in use for making Bhel (Credit-Bio Basics)

Poongar, another red rice grown in Tamil Nadu is called the women's rice. According to oral knowledge shared by farmers, this rice has

properties to help women overcome many a health problem ranging

from gynaecological issues to joint pains.

Ilupai poo samba, a white rice that is had as

kanji is again preferred by women and used to be regularly consumed by them in

the Thanjavur rice growing belt. With a faint fragrance this rice kanji is

filling and delicious, it gets its name. I distinctly remember during our

travels through Thanjavur visiting rice farmers, unexpectedly I developed a

fever, this was the time we reached the home of Ashokan Anna, who grow Ilupai Poo samba. His wife gave me a cup

of Ilupai poo samba Kanji, I asked for a second cup despite the fever, as it felt

very soothing and light and kept me going.

Iluppai Poo Samba Rice (Credit-Bio Basics)

Iluppai Poo Samba Rice (Credit-Bio Basics)

In

Karanataka, Rajamudi rice, one of the varieties preferred by the Wodeyar kings is being revived

by farmers and is gaining popularity. A mix of red and white grain, this is

excellent for table rice and also making variety rice. It is a preferred as it

has the property to mix with the gravies and absorb the taste making it a

delicious table rice suitable for South Indian meals.

Rajamudi Rice (Credit-Bio Basica)

Rajamudi Rice (Credit-Bio Basica)

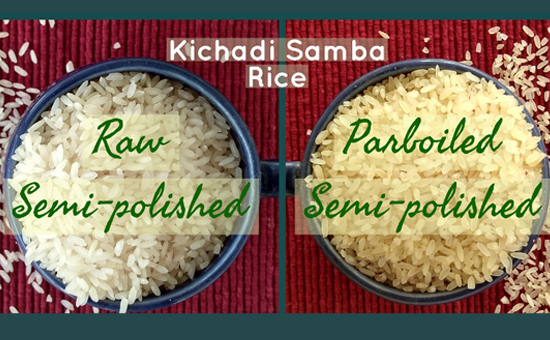

We at Bio Basics also offer two traditional white

rice varieties from Tamil Nadu - Kichadi Samba and Thooyamalli. Both have excellent cooking quality and are equally good as parboiled rice or raw rice. I personally

prefer Kichadi Samba because of its

sweetness. These rices are great for making variety rice as well.

Khichdi Samba Rice (Credit-Bio Basics)

Khichdi Samba Rice (Credit-Bio Basics)

Jeeraga Samba, known as the Basmati of the

South is a

slender, aromatic rice, very popular in Tamil Nadu and Kerala. It is one of our

favourites. One of the peculiarities I have found is that the rice doesn’t go bad, kept outside and is good enough to

be eaten the next day. In fact, this is the case with many

traditional rice varieties. Since the traditional varieties I have consumed are

all grown organically I do not know if this is due to the absence of synthetic

chemicals used in growing or due to the inherent property of the rice

variety.

Some Fragrant Rice Varieties (Photo Credit - Bio Basics)

Some Fragrant Rice Varieties (Photo Credit - Bio Basics)

The Gobinda Bhog aromatic rice from West Bengal, small grained, sticky, with an aroma is

delicious to make kheer (payasams) or any sweet. I love this rice for just

plain rice also; it makes any side dish palatable and just goes down the throat

like a fragrant breeze.

How can I

forget the Mullankazhama, the aromatic rice that had almost disappeared from the fields and our

plates, but has fortunately been revived? Neither slender nor small, this round

grained unusual looking aromatic rice has a unique flavour and is preferred for

making the Malabari

Biriyani. Like every other aromatic rice this is also excellent for

making desserts.

The medicinal rices are an altogether different class.

Each has its own property, from dealing with acne to arthritis to pregnancy

related issues to cancer to headaches to skin infections to stomach upset to

heartburn and much more. Navara being the most well-known, used extensively in

Ayurveda for external use as kizhis

and also for consuming as kanji.

This is not the only one; Valiya

Chennelu, Raktasali, Karibhatta and numerous others are a storehouse

of curative properties. And this is not even the tip of the richness that is

available.

How about trying some traditional rice varieties?

The farmers

are doing their bit of growing diverse varieties, under organic conditions and

bringing it to us with minimal processing. Now what do we have to do? I suggest

we stop outsourcing the most important task in our life - how and what to feed

our families and ourselves.

We are

happy to try out new cuisines, variations of existing cuisines. Then why do we

hesitate to try out a new rice? We know our taste buds have a life span of twenty

one days and we can get used to any new food. So, why don’t we try the various rice varieties?

Traditional

Rice Varieties - Raw & Parboiled (Photo Credit - Bio Basics)

Traditional

Rice Varieties - Raw & Parboiled (Photo Credit - Bio Basics)

It is only when we connect to farming, farmers and

food can we understand the inextricable relationship we have with the

traditional rice varieties of our region. Today with modern

transportation, we also have the privilege of trying rice varieties from

different regions. The commitment of the seed saver farmers should be

matched with our passion to incorporate these varieties into our diets.

If we devote some

time to experiment with these varieties, if we can commit some time to prepare

innovative , tasty dishes with unpolished/semi polished rice we would be spared

the difficulty of cutting it out of diets, for fear of diabetes and obesity.

Paddy

rice is not the culprit, we are the culprits,

we polish the rice beyond recognition, we do not try out the range of

traditional rice varieties with diverse nutritive profiles, and we do not try

new and interesting ways of preparing and making them popular. In any case, all

of us from rice growing regions love rice. Like the farmers who have begun

conserving out of sheer love for the grains, let us do our bit to learn more,

prepare more varieties and adopt them into our diets in a healthy and delicious

form.

This is

just the story of rice; we have similar deep

diversity in millets, wheat, pulses, and so on. What we need to do is

eat our way into diversity. Only if we eat

diversity will the farmers grow it. Only if the farmers grow these

diverse varieties of these diverse crops – this agri-biodiversity – can we maintain

and carry forward this heritage of seeds, which is the collective wealth of

humankind.

Author is the

Co-Founder of Bio Basics, a social venture retailing organic food and a

Consultant to the Save Our Rice Campaign.

Also read

1 Why the rise of local grains is

not just about health

“Every

region and tribal belt in India has its own local variety and preparation style

of millets. While jowar and bajra are popular

in the West, grains like oodhalu (barnyard millet) and navane (foxtail

millet) are more popular in the South. In fact, some of these hardy grains have

been mentioned in our ancient texts like the Yajurveda, which talk

about agriculture, economic and social life during the vedic era. Yet, their

consumption and cultivation had been on the decline for the better part of the

last century. In 2016-17, the area under millets stood at 14.72 million hectares,

down from 37 million hectares in 1965-66, before the pre-Green Revolution,

according to a March report by Hindu Business Line.” Article

excerpts published in MINT newspaper.

2 How Andhra

Pradesh is taking to natural farming

3 Native seeds are

a key to food security

4 Sangrur Punjab:

A Harvest of Distress

5 Madhya Pradesh

farms a green revolution

6 Virtues of Drip

Irrigation

7 India’s Constant

Gardeners

8 The rise of MILLET